The Deepwater Horizon Spill, Four Years On.

This week, for the first time since 2010, researchers will travel to the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico to get a first-hand look at the site of the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster. In April 2010, a blowout at BP’s Macondo oil well resulted in the deaths of eleven rig workers and the largest offshore oil spill in U.S. history. To continue their study of the effects, researchers will travel as deep as 7,200 feet, more than one mile down, in the Human-Occupied Deep Submergence Vehicle Alvin, the same submarine that located a lost hydrogen bomb off the coast of Spain in 1966 and surveyed the wreckage of the Titanic in 1986. I will be the only journalist to participate in any of these dives (I’ll do three) and to spend two weeks participating in this historic deep-sea research cruise.

This week, for the first time since 2010, researchers will travel to the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico to get a first-hand look at the site of the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster. In April 2010, a blowout at BP’s Macondo oil well resulted in the deaths of eleven rig workers and the largest offshore oil spill in U.S. history. To continue their study of the effects, researchers will travel as deep as 7,200 feet, more than one mile down, in the Human-Occupied Deep Submergence Vehicle Alvin, the same submarine that located a lost hydrogen bomb off the coast of Spain in 1966 and surveyed the wreckage of the Titanic in 1986. I will be the only journalist to participate in any of these dives (I’ll do three) and to spend two weeks participating in this historic deep-sea research cruise.

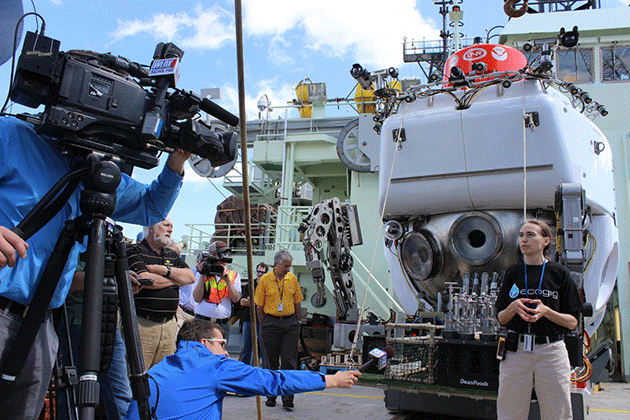

On March 29, I joined several TV, newspaper, and wire reporters for a tour of the newly upgraded sub on board the Atlantis research vessel, which was docked in Gulfport, Mississippi, the day before departing for a nearly month-long series of investigations. In addition to the Alvin, the Atlantis is equipped to carry six science labs, seafloor-mapping sonar, satellite communications, winches, cranes, a machine shop, a crew of thirty-six, and more than two dozen scientists. Both the Alvin and Atlantis are owned by the U.S. Navy and operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute.

The Alvin is a round squat bubble, painted white except for a red top hatch and large silver jutting metal arms, giving it the impression of a somewhat menacing robotic marshmallow with a cherry on top. With the Alvin as a backdrop, Samantha Joye, the expedition’s chief scientist and a biogeochemist oceanographer at the University of Georgia, explained the coming cruise.

The submersible will revisit sites near the Macondo wellhead that Joye’s team observed in 2010 to be heavily impacted by oil, as well as newly identified ones. Research on that and subsequent trips also helped to identify the underwater plumes of Macondo oil that were floating deep in the sea. The goal this time will be to document and discover the ongoing impacts of the disaster, including how much oil remains; what has happened to the gulf, its sea life, and its ecosystems; and what the long-term impacts of this and other oil spills might be. “Just because people do not see as much oil on beaches,” said Joye, “does not mean the impacts of the oil spill are in the past.” In fact, barely a week ago some 300 pounds of Macondo oil washed up as tar balls on two Mississippi beaches because of low tides and high winds, according to local officials.

The team of eight senior researchers is also planning to visit sites marked by sedimented oil and deep-sea hypersaline brine seeps — “very strange early earth environments that support bizarre forms of microbial life,” Joye explained of the latter. They will identify the novel (and in many cases unknown) organisms that survive in these hostile environments. The sites, she said, are “ideal analogs for earth’s early oceans and early types of microbial life and metabolisms, which tells us how all life evolved.”

The Alvin will dive twenty-two times during the cruise, at a cost of approximately $65,000 per dive. The voyage is being funded by the National Science Foundation and ECOGIG (Ecosystem Impacts of Oil and Gas Inputs to the Gulf), a research consortia funded by a $500 million commitment BP made to independent research programs under pressure from the White House and Congress following the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

The expedition takes place just as the legal battles against BP approach a crucial stage, notably the Justice Department’s litigation against the company over exactly how much oil spilled from the Macondo well, what has happened to it, how much damage it has caused, what the long-term consequences will be, and how much money BP owes as a result. The next stage of the trial is set to begin in New Orleans in January.

Despite the legal fight, just this month the U.S. government lifted the ban it imposed on BP in 2010, which barred the company from bidding on government contracts. Within a week, BP participated in an auction for new Gulf oil-drilling leases, reportedly winning twenty-four bids, including some for areas near the Macondo well.