Sustainable Solutions to the Climate Crisis

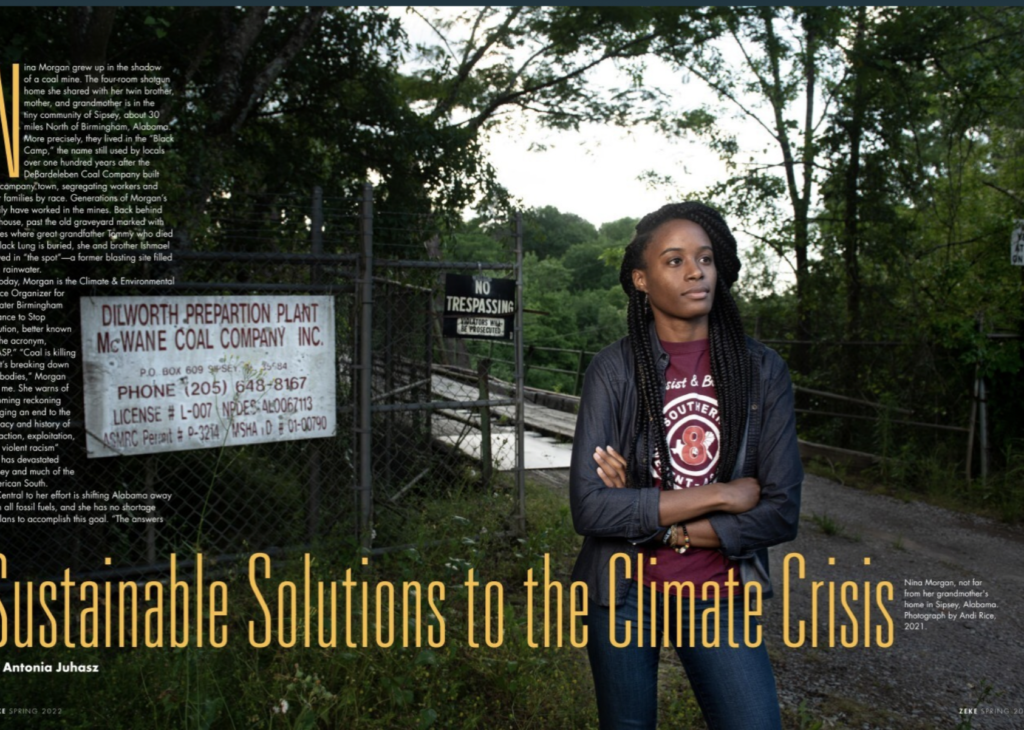

Nina Morgan grew up in the shadow of a coal mine. The four-room shotgun home she shared with her twin brother, mother, and grandmother is in the tiny community of Sipsey, about 30 miles North of Birmingham, Alabama. More precisely, they lived in the “Black Camp,” the name still used by locals over one hundred years after the DeBardeleben Coal Company built this company town, segregating workers and their families by race. Generations of Morgan’s family have worked in the mines. Back behind the house, past the old graveyard marked with stones where great grandfather Tommy who died of Black Lung is buried, she and brother Ishmael played in “the spot”—a former blasting site filled with rainwater.

Today, Morgan is the Climate & Environmental Justice Organizer for Greater Birmingham Alliance to Stop Pollution, better known by the acronym, “GASP.” “Coal is killing us. It’s breaking down our bodies,” Morgan told me. She warns of a coming reckoning bringing an end to the “legacy and history of extraction, exploitation, and violent racism” that has devastated Sipsey and much of the American South.

Central to her effort is shifting Alabama away from all fossil fuels, and she has no shortage of plans to accomplish this goal. “The answers are already there,” Morgan explains. “People in Birmingham have been thinking about this for years.”

The plans start with shutting down coal operations in Sipsey and coke plants (an industrial byproduct of coal) in Birmingham, employing locals to clean up the sites and surrounding neighborhoods using bioremediation, establishing local community owned and operated solar and agricultural farms, and passing a local Green New Deal. The sustainable solutions are clear, the problem is “the political will and the money to really scale it,” Morgan says.

Morgan’s experience and analysis is repeated in interviews and investigations I’ve conducted across decades and continents. There is little mystery about how to achieve sustainable solutions to the climate crisis; to the contrary, people are now and have been implementing them for millennia. Our planet is increasingly inhospitable to us not because we lack the resources to provide for our people, but rather because a small percentage of them have adopted devastatingly harmful, often-times racist, fossil fuel-led lives, which are, in fact, relatively simple to adjust. The problem is not one of technology. Instead, it mostly boils down to power and politics: primarily a few governments and companies, and of course some consumers, who just refuse to let go.

In many ways, this is a profoundly hopeful message. We know the problem, have had the means to solve it, and we’re even having a great deal of success—albeit not nearly enough.

Fossil Fuels are Obsolete

Fossil fuels are the leading cause of the climate crisis. The fossil fuel industry and its products account for 91% of global industrial greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and about 70% of all human-induced climate emissions. In the U.S., fossil fuels account for 94% of total carbon dioxide emissions and 80% of all GHG emissions from human activity. As a result, the International Energy Agency recently concluded that if we are to meet the Paris Climate Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, there can be no new investments in fossil fuel production anywhere.

We not only know the “what” of the climate crisis, but also the “who.” Since 1988, more than half of all global industrial GHG emissions can be traced to just 25 fossil fuel companies, including ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP, and the national oil companies of Russia, China, and Saudi Arabia. The lack of progress on international policies to curb climate emissions are due in small part to the actions of these companies and countries (including the corporate host nations of the U.S. and Britain).

Azeb Girmai is the climate policy lead for LDC Watch International, a network of civil society organizations advocating on behalf of the 48 Least Developed Countries (LDCs) in the world. On December 10, 2015, I sat across from Girmai on the outskirts of Paris at the Le Bourget conference center. Girmai made the trek from Ethiopia, then-gripped by a deadly and crippling drought, its worst in 30 years. Around us swirled a polite cacophony of activity — regularly punctuated by the shouts of protestors chanting “1.5 to stay alive!” or “Keep It In The Ground!” — as thousands gathered to influence the outcome of what would emerge two days later as the Paris Climate Accord.

Girmai conveyed both hope and urgency as she shared her message to negotiators. Africans, who have done the least to cause the climate crisis but are suffering the worst of its impacts, have solutions, but they need support. She described local initiatives to allow Africans to leapfrog the fossil fuel stage of development and overcome the increasing hardships of global warming, including providing individual homes across rural areas with simple easy-to-use wind and solar energy kits. Localization and democratization of energy are key, particularly for women. Energy access “is the game changer for women in Africa,” Girmai said.

Funding for climate change efforts is not only woefully inadequate, but also less than 10% of the $17.4 billion in climate finance from leading international institutions between 2003 and 2016 targeted local initiatives such as Girmai’s. Climate finance, particularly the significantly larger sums spent by corporations, venture capital, and private equity, instead flows to large-scale centralized mega-projects frequently focused on the “next big technological fix” to the climate change problem.

A few days before I spoke with Girmai, Leonardo DiCaprio, then serving as the United Nation’s Messenger of Peace, addressed a gathering of world leaders at the Paris City Hall. He shared a similar message to Girmai’s. “Our future will hold greater prosperity and justice when we are free from the grip of fossil fuels,” he said.

He cited the work of Stanford Professor Mark Jacobson who demonstrated in 2009 that fossil fuels are obsolete. “We can meet the world’s energy demand with 100% clean renewable energy using existing technologies by 2050,” DiCaprio explained, referring to all forms of energy consumption replaced with wind, water, and solar. He urged the gathered elected officials to do their part by quickly enacting policies to support a transition to low carbon transportation, energy efficient buildings, better waste management, and renewable energy.

Six year later, COP26 in Scotland resulted in disappointment, but also some important achievements, including the launch of a “Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance” by 12 governments to “end all oil and gas production and exploration” on their territories.

Professor Jacobson points to 10 countries (with four on their way) with 97.5-100% electricity powered exclusively by renewables and laws on the books in 61 countries to meet that target. Around the world, 180 cities, including in eight U.S. states, have formalized plans to reach 100% renewable energy for electricity and over 100 already get at least 70% exclusively from renewables.

A recent Oxford University study finds that a rapid shift to wind, solar, and other zero-carbon technologies would save the world $26 trillion in energy costs alone (including the cost to adapt the electricity grid) while at the same time meeting the Paris Climate Accord targets. Solar, wind, and other zero-carbon technologies have been decreasing in cost overtime—with solar 2,000 times cheaper today than at its first commercial use in 1958—while fossil fuels are as expensive to produce and consume today as they were 150 years ago.

Moving energy through renewables is also more efficient than fossil fuels. Merely electrifying the energy sector reduces overall energy demand by nearly 60%, Jacobson finds. And the closer you place the user to the source of energy – i.e. localized wind and solar – the less energy is needed. Investments in public transportation should trump individual cars. To further reduce overall resource extraction of feedstocks such as lithium for batteries, Jacobson stresses the ability and necessity to increase both their recycling and reuse.

There are innumerable human health and climate benefits to be won when particularly the heaviest users shed the shackles of unsustainable energy demand.

Indigenous Communities are Living the Alternative

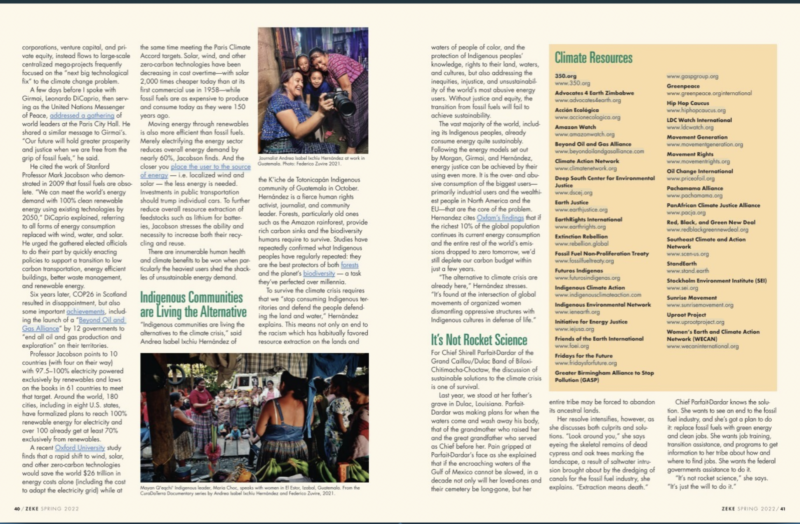

“Indigenous communities are living the alternatives to the climate crisis,” said Andrea Isabel Ixchíu Hernández of the K’iche de Totonicapán Indigenous community of Guatemala in October. Hernandez is a fierce human rights activist, journalist, and community leader. Forests, particularly old ones such as the Amazon rainforest, provide rich carbon sinks and the biodiversity humans require to survive. Academic studies repeatedly confirmed what Indigenous peoples have long known to be true: they are the best protectors of both forests and the planet’s biodiversity – a task they’ve perfected over millennia.

To survive the climate crisis, requires that we “Stop consuming Indigenous territories and defend the people defending the land and water,” Hernandez explains. This means not only an end to the racism which has habitually favored resource extraction on the lands and waters of people of color, and the protection of Indigenous peoples’ knowledge, rights to their land, waters, and cultures, but also addressing the inequities, injustice, and unsustainability of the world’s most abusive energy users. Without justice and equity, the transition from fossil fuels will fail to achieve sustainability.

The vast majority of the world, including its Indigenous peoples, already consume energy quite sustainably. Following the energy models set out by Morgan, Girmai, and Hernandez, energy justice can be achieved by their using even more. It is the over- and abusive consumption of the biggest users—primarily industrial users and the wealthiest people in North America and the EU—that are the core of the problem. Hernandez cites Oxfam’s findings that if the richest 10% of the global population continues its current energy consumption and the entire rest of the world’s emissions dropped to zero tomorrow, we’d still deplete our carbon budget within just a few years.

“The alternative to climate crisis are already here,” Hernandez stresses. “It’s found at the intersection of global movements of organized women dismantling oppressive structures with Indigenous cultures in defense of life.”

It’s Not Rocket Science

For Chief Shirell Parfait-Dardar of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, the discussion of sustainable solutions to the climate crisis is one of survival.

Last year, we stood at her father’s grave in Dulac, Louisiana. Parfait-Dardar was making plans for when the waters come and wash away his body, that of the grandmother who raised her and the great grandfather who served as Chief before her. Pain gripped at Parfait-Dardar’s face as she explained that if the encroaching waters of the Gulf of Mexico cannot be slowed, in a decade not only will her loved-ones and their cemetery be long-gone, but her entire tribe may be forced to abandon its ancestral lands.

Her resolve intensifies, however, as she discusses both culprits and solutions. “Look around you,” she says eyeing the skeletal remains of dead cypress and oak trees marking the landscape, a result of saltwater intrusion brought about by the dredging of canals for the fossil fuel industry, she explains. “Extraction means death.”

Chief Parfait-Dardar knows the solution. She wants to see an end to the fossil fuel industry, and she’s got a plan to do it: replace fossil fuels with green energy and clean jobs. She wants job training, transition assistance, and programs to get information to her tribe about how and where to find jobs. She wants the federal governments assistance to do it.

“It’s not rocket science,” she says. “It’s just the will to do it.”