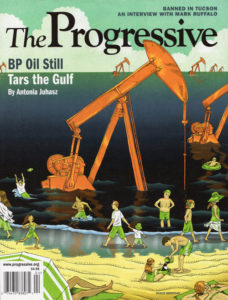

BP Oil Still Tars the Gulf

For many Americans, the story of the BP disaster began on April 20, 2010, and ended on August 15 of that year, when the Obama Administration declared that “the majority of the oil is gone,” though the opposite was true.

For those on the Gulf Coast, the disaster remains, and life continues to be measured in terms of “before” and “after” the BP oil spill. They are tired of it all: BP, the government, the lies and the lawyers, the hardship and the illness, the oil on the beach and in the water, the dead dolphins and the disfigured fish, the ever-shrinking hauls of oysters, crab, and shrimp, and the rest of the nation’s cold shoulder. They still don’t know the answers to many life-and-death questions. But they keep going, hoping for life to return to the way it was before.

I’m driving toward Grand Isle, Louisiana, with microbiologist and toxicologist Wilma Subra. We enter the tiny town of Larose, where we see the Southern Sting Tattoo parlor. Wilma and I had taken this same drive a year and a half earlier. In the interim, the façade has changed, but not the underlying concerns.

Shortly after the spill, artist and owner Bobby Pitre transformed his parlor into a gateway of shame for BP and a challenge to President Obama. It became an iconic image of the oil spill, appearing frequently in news reports. But now the signs are gone and Bobby is once again serving up tattoos, not despair.

“It’s nearly two years in and the oil spill remains a constant in everyone’s life,” he tells me. “I’m a surfer, and I haven’t been in the water since this happened. Lots of people still aren’t working. I don’t want to turn a blind eye and say it’s all peaches and cream, but you got to get away from it sometimes for your soul, you know? We just want to go back to business as normal.”

Back to normal may not be possible for the families of the eleven men who died aboard the Deepwater Horizon. But they, too, press on.

Gordon Jones, a mud engineer for drilling service contractor M-I SWACO, was killed on the Deepwater Horizon. He was just twenty-eight years old and preparing for the birth of his second son, Maxwell Gordon Jones, who was born in May 2010. His brother, Stafford, was two years old at the time.

I join Gordon’s father, Keith, and Gordon’s stepmother, Sandra, at their Baton Rouge home. Before I even sit down, they beam, handing me new photos of Maxwell and Stafford.

Keith speaks of an evening when Stafford stood on top of a chair to get a better look at a photograph of his father teaching him golf. Stafford began to talk to the photo. “He just was having a quiet conversation with his dad,” says Keith, his voice trailing off.

Since his son’s death, Keith has made it his mission to ensure that his family—and the families of all those who died aboard the rig, and every other family that suffers a similar fate—is provided just support from the company at blame. This has meant a tireless and thus far unsuccessful effort to get the U.S. Congress to amend the Death at High Seas Act. But Keith is not done trying.

Keith has also waged an unrelenting fight to ensure that BP is brought to justice. “Everything that BP did that led to this blowout—everything, I mean everything—was done to save money or to save time,” Keith tells me. “If time is money, then it was all about money. Halliburton made some mistakes; Transocean made some mistakes. But this was BP’s rig, and they had the final say on everything. And every decision they made was about greed. It’s that simple.”

Unlike Transocean and M-I SWACO, BP has not offered a single word of condolence, card, flower, or even a handshake directly to Keith or any member of his family for their loss, he says.

But BP has spent a lot of money selling the idea that all is back to normal in the Gulf. In many ways, for BP at least, it is. In 2011, BP racked up its highest profits of all time: a jaw-dropping $25.7 billion. BP was, and remains today, the number one producer of oil and gas in the Gulf of Mexico. The first new lease for deepwater drilling in the Gulf that the government issued following the disaster went to BP (with 53.5 percent majority partner Noble Energy).

On May 30, 2010, a moratorium on deepwater drilling in the Gulf temporarily halted 33 of the 103 rigs operating at that time. On October 12, 2010, the moratorium was lifted, work quickly resumed, and today 113 rigs operate in the Gulf, 40 of which are in the deepwater, up from 37 at the time of the spill.

Large amounts of federal and state waters were closed to fishing in the wake of the spill, many areas for more than a year and a half. Once reopened, many were devoid of the seafood they once supported or inhospitable to the spawning of new life.

Byron Encalade is president of the Louisiana Oystermen’s Association. He lives in the predominantly African American fishing community of Pointe à la Hache, Louisiana. “These bayou communities, including ours, are suffering still two years after the oil spill,” Byron tells me. “Our local economies are gone. We are devastated. You don’t need a rocket scientist to determine that if someone is a fisherman, and they can’t fish, that they’ll be hurting!”

In Louisiana and Mississippi, oyster production collapsed, falling by 55 percent in Louisiana and 34 percent in Mississippi from 2009 to 2010. Even lower numbers are expected when the 2011 harvest is tallied.

Byron operates out of Bay Jimmy, where, he reports, oil continues to come up on land, in the water, and in critical reef habitats. Byron’s biggest fear is production. “We’ve already been out two years. My concern is that there’s no spat [larval oysters] out there, so that means we’re out another two years. What are we supposed to do then?”

Shrimpers are facing an only slightly less daunting situation, as Clint Guidry, president of the Louisiana Shrimp Association, tells me over breakfast in New Orleans.

Between 2009 and 2010, the shrimp crop declined in Mississippi by 52 percent, in Alabama by 48 percent, and in Louisiana by 14 percent, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “Coming into late September 2011 our crop was down by 80 percent,” Clint tells me. “The areas with the least amount, and in some cases, no shrimp are those hardest hit by the oil and dispersant.”

“Bottom line? Our guys are still hurting,” says Clint. “And we’re very concerned for the future.”

The hub of seafood production in the Gulf is the tiny coastal town of Bayou La Batre, Alabama, population 2,500, otherwise known as “the seafood capital of Alabama.”

In January, I am heartened to say goodbye to another iconic image of the BP oil spill.

Throughout 2010, it seemed that every green fishing net in the Gulf had been replaced with bright yellow and orange plastic tubes to capture oil instead of seafood.

But on this trip, wherever I go, the green nets are back.

I share my excitement with twenty-seven-year-old David Pham, program director at Boat People SOS, a central hub for community members seeking assistance in response to the spill. David looks a bit astonished and replies, “Yeah, it’s great that they have their nets on, Antonia. But they’re still docked in the harbor. They’re supposed to be out in the Gulf catching seafood.”

Photo: Flickr Creative Commons – Florida Sea Grant

Prior to the spill, an estimated 80 percent of the workforce of Bayou La Batre made its living from the commercial seafood industry. A large percentage of this workforce is of Southeast Asian descent, primarily from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

David estimates that only about half of the seafood processing facilities have reopened, and more than 50 percent of the town’s seafood workers and fishers are back at their jobs, albeit for far fewer hours.

Rot Thi Lam, fifty-eight, has worked in crabbing facilities for more than a quarter of a century. Thi Lam speaks Vietnamese, so her son Vinh Tran explains her situation to me. She is able to work only half as much as she did before the spill and half as much as she needs to. The family is “making do,” Vinh says, but it is not easy.

In November 2010, Vinh’s mother accepted the “final payment” offered by the Gulf Coast Claims Facility (GCCF), the fund administered by Obama Administration appointee Kenneth Feinberg for claims against BP. Claimants were given a one-time offer to either petition the GCCF for a determination on past and future losses or accept the final payment for $5,000 for individuals and $25,000 for businesses. The catch for accepting the final payment was forgoing the right ever to sue BP.

According to David, most of the Bayou’s Vietnamese residents took the final payout. The same is true of many of the oystermen Byron Encalade knows. People had bills stacking up, and they could not afford to wait.

“The claims process was just so frustrating and difficult,” David says. “Most just wanted to be done with it. I think for the most part people are just tired.”

But the final payments did not go far. David estimates that about 10 to 15 percent of the Asian community, primarily the elderly, left Bayou La Batre for good because of the oil spill.

The future weighs heavily upon him. “When you don’t have that much seafood anymore,” he asks, “what are we the capital of now?”

United Houma Nation tribal member Jamie Billiot is thirty-two years old and has lived on the shores of the Gulf Coast her entire life, just as her father, her father’s father, and a hundred years of her tribe’s people before her. She lives in Dulac, deep in the bayou on one of Louisiana’s “fingers”—strips of land that jut into the Gulf. Jamie served previously as executive director of the Dulac Community Center.

“The tribe eats what we catch,” Jamie tells me. “Today, whether it’s shrimp, oysters, or crab, there’s less to catch, less to eat, and less to sell.” This means people have to turn to grocery stores to supplement their diet, making it harder to afford other basic needs.

From 2009 to 2010, the crab crop declined by 42 percent in Louisiana, 37 percent in Alabama, and 33 percent in Mississippi.

“Can we completely recover from this?” Jamie asks me, “Probably not. At what level will we recover? I don’t know. If the oyster beds no longer produce, the shrimp migrate away, land loss continues. . . . ” Jamie pauses before she speaks again. “It will take years for us to really know.”

They also worry about the safety of the meat. “Crabs and oysters get everything from the water,” Jamie explains. “So, can we trust them?”

The short answer for Jamie, her three-year-old daughter, Camille, and their family is most likely no, based on the research of scientist Miriam Rotkin-Ellman of the Natural Resources Defense Council and her colleagues Drs. Karen K. Wong and Gina M. Solomon. Writing in the National Institutes of Health’s Environmental Health Perspectives journal, they identify numerous problems with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) assertion that Gulf seafood is safe for all to eat.

The FDA assessment is based on a 176-pound adult (75 percent of women in the United States weigh less than this) eating a diet based on national, rather than local Gulf Coast, characteristics, a weekly diet consisting of just one type of seafood and, for shrimp, a total of just four jumbo shrimp. People in Gulf states, particularly those who live on the coast, typically eat multiple types of Gulf seafood per week, if not at once (think gumbo), and eat it every day, often several times a day.

“The FDA [also] does not account for the fact that children are known to be more vulnerable to contaminants in seafood because they eat more per pound of their bodyweight and their developing bodies are more sensitive to harmful contaminants,” Dr. Solomon writes on her blog. “What’s more, in a pregnant woman, these contaminants can cross the placenta and harm the developing fetus.”

The FDA set a lower bar for acceptable cancer risk than the one following the Exxon Valdez oil spill: one cancer incidence in one million people in five years versus one in one million in ten years.

It is impossible to accurately determine the safety of Gulf seafood for anyone, Rotkin-Ellman tells me, without a more robust model.

Seafood is only one among many threats to human health caused by the disaster. Other threats include the hundreds of “controlled burns” of BP’s oil on the ocean’s surface from April 28, 2010, to July 19, 2010. When I first met Jamie in mid-2010, she described smelling the burning oil before ever seeing it. The smell was “unnatural,” she recalled. “It was terrible.”

Her father, James, told me that when the oil burns took place, “It was like standing next to a motor car running all day.” And he made a dire prediction: “Just wait and see. In twenty years, we’re going to have the highest cancer rates you ever seen.”

Over a year and half later, Jamie tells me that she, her father, her godfather, and many others regularly experience cycles of bronchial problems that last for months on end. They cough, can’t get enough air, just feel sick, and stay sick longer. They’d never experienced this before. “People are getting sick and they are staying sick,” she says. “It’s not normal.”

People across the Gulf are suffering from a long list of ailments consistent with exposure to the pollutants and toxins in oil and chemical dispersants. As Wilma Subra and others have documented, these include headaches, nausea, respiratory problems (including asthma attacks), irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat, rashes and irritated, itching, and even burned skin, and, in rare cases, neurological impacts, including memory loss.

Of particular concern are the large numbers of children suffering frequent bronchial and stomach ailments and skin rashes. Those who live nearest the spill site have had the highest incidence.

Humans aren’t the only ones getting sick. So, too, are the region’s fish. Dr. James H. Cowan Jr., of the Department of Oceanography and Coastal Sciences and the Coastal Fisheries Institute at Louisiana State University, has found a decline in the diversity and abundance of different fish species since the spill. He also has found fish with secondary infections that are indicative of compromised immune systems. Typical are lesions on livers, skin lesions, ulcers, and high parasite infestations that are much higher than normal, he tells me. In some areas with cumulative surface oiling after the spill, he found some sites where as many as 50 percent of fish caught had lesions and sores. He estimates that about twenty fish species have been identified thus far as suffering these impacts.

Dr. Darryl Felder of the Department of Biology at Louisiana State University has similarly observed high incidence of spots, lesions, and species decline since the spill among the tiny crustaceans (crabs, shrimp, and lobsters) of the deep Gulf waters. His biggest fear, he tells me, is “ecosystem collapse.”

Larger mammals have also been impacted. In February 2011, during the first dolphin calving season in the wake of the spill, dozens of dead baby dolphins and aborted fetuses washed up on Gulf beaches. Normal death rates are just one or two a season.

In reefs closest to the spill site, Dr. Cowan reports, “What’s missing, in some areas completely, are a lot of the small species that occupy the bottom third of the water column and come into lots of contact with the seafloor.” The reason? “This is where BP’s oil has settled,” he tells me.

On the road to Grand Isle in January, Wilma Subra and I stop at Elmer’s Island. There we find large fresh globs of oil mixed with seaweed and in the shells of oysters. We also see fresh oil floating in the water, as well as oiled fish.

Last August, Tropical Storm Lee swept through the Gulf Coast, carrying fierce waves, wind, rain, and BP’s oil. On August 13, Jason Berry found upwards of 100 “tar logs” on Mississippi’s Ship Island, heavy cylinder-shaped mounds of tar that look like a log you’d throw on the fire.

According to the Louisiana Environmental Action Network, an independent lab confirmed the logs’ composition to be BP oil. Jason tells me via e-mail that similar logs have washed up in other areas. “What that tells us,” he argues, “is that the sea floor is probably covered with these logs. The oil is most likely rolling along the seafloor like tumbleweed and forming them.”

On my last day in the Gulf Coast, I drive to Bon Secour National Wildlife Refuge in beautiful Gulf Shores, Alabama. There I encounter several vacationers. I ask Flora Weatherby and Al Penny of Rochester, New York, if they’d seen any oil. No, they say. Three fishermen from Chesaning, Michigan, give the same response.

After chatting a bit, I walk about five steps up the beach to where the previous wave break has most recently crested. Lo and behold, mixed in with the seashells, I find oil tar balls the size of dimes and quarters.

“Would it surprise you that there are tar balls right behind you?” I ask Bob Culp, one of the fishermen. “Yes, it certainly would,” he replies. After I show them to Bob, he says they make him “sad. And mad.” He reflects a moment, and then starts talking about BP. “You know,” he says, “they have to keep cleaning this beach. If it takes ten years, it’s their responsibility. Mother Nature can only do so much.”

When I show Flora, she begins to cry. Al says, “All we see are those commercials, and all we see is BP’s side. If it took you fifteen seconds to find this, what else is out there?”

To date, not a single piece of legislation written in response to the BP oil disaster has become law. That is not for lack of trying.

Gulf Change, a group of local impacted community members, stages monthly protests.

Casi Callaway, the intrepid executive director of Alabama’s Mobile Baykeeper, works with a broad network of organizations to bring restoration and long-term recovery to the Gulf. Like so many others I speak with, she often feels alone in these efforts, all but forgotten by the rest of the country.

I ask Casi to tell me the first thing that comes to mind when reflecting on the two-year anniversary of the spill. She replies: “Please God, can I go to the beach again with my kid and feel safe? But the second thing is, with the Exxon Valdez, it took years before the full effects were felt. What are we going to lose? And who’s going to be watching?”