Dirty Politics

“You won’t believe how much money we spent in the last two hours.” — A White House official, speaking anonymously to Congress Daily, shortly before the House vote on renewing Fast Track.

“You won’t believe how much money we spent in the last two hours.” — A White House official, speaking anonymously to Congress Daily, shortly before the House vote on renewing Fast Track.

The year 2001 was, to say the least, a tumultuous year for the opponents of corporate-led globalization. There were many high points, such as the gathering of over 10,000 people from across the world in Porto Alegre, Brazil to discuss positive alternatives to corporate-led globalization. Then, there were the 60,000 people moved to take to the streets in Quebec City, Canada to protest the creation of the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA). At the same time, even before the horrendous tragedies of September 11, there were extreme lows, the worst being the deaths of four anti-globalization protestors at the hands of police on the streets of Genoa, Italy and Papua New Guinea.

However, it was clear throughout the year that the anti-globalization movement had fundamentally shifted the debate on globalization from one of “how fast?” to “for whom and at what cost?” Just as this shift in thinking had begun to affect the shape of public policy, the tragedy of September 11 occurred. Nothing could have prepared the anti-globalization movement—or anyone—for the events of September 11 and their aftermath. But neither could we have foreseen the sort of dirty politics carried out in the name of fighting terrorism that would be used by the Bush administration and the Republican leadership to achieve its 2001 corporate globalization “victories:” the launch of a new round of negotiations at the World Trade Organization (WTO) and passage of Fast Track in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Immediately following the events of September 11, the Bush administration began to argue that terrorism could be fought with trade. The first step would be Fast Track—the darling of the corporate world, denied to it for seven years by a coalition of legislators and human rights, women’s, environmental, consumer, and labor organizations. “Fast Track” is a mechanism by which Congress eliminates many of the key democratic processes it uses to create legislation—including the full committee process, full debate, and the ability to amend legislation. Opposition to Fast Track has grown steadily in and outside of Congress primarily in response to the legislation that it has been used to pass—most recently, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the establishment of the WTO. After experiencing the impact of these agreements, few in the United States were eager to so readily turn over their democratic rights to aid in the creation of such legislation in the future. So, when President Bush and his trade representative, Robert Zoellick, started emphasizing Fast Track as a response to terrorism, few thought the argument would go far. In fact, the legislation remained stalled until the success of the fourth WTO ministerial meeting held in the small dictatorship of Doha, Qatar in the Persian Gulf.

Erasing the “Stain of Seattle”

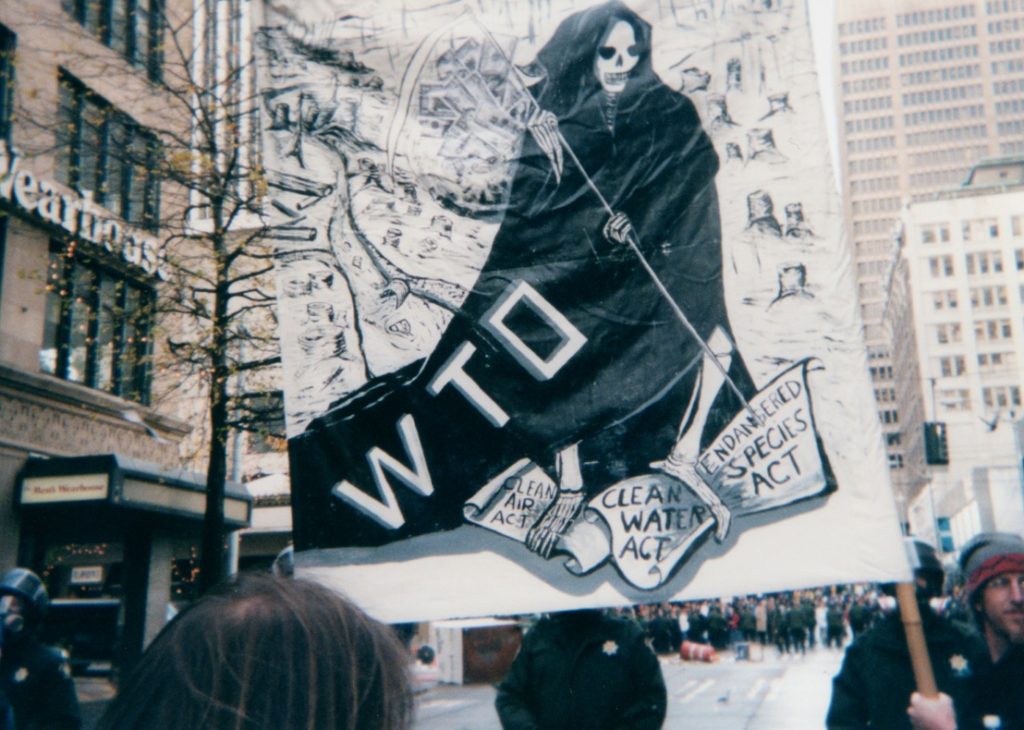

In December 1999, the WTO tried to hold its third ministerial meeting in Seattle, Washington. The WTO was unable to launch a new round of trade liberalization negotiations at this meeting because of the 50,000 people on the streets of Seattle who brought sunshine to a traditionally secret backroom process. The sunshine made it impossible for the WTO delegates do the arm-twisting and undemocratic deals for which the organization is renowned. Even more importantly, developing country delegates stood up to the “Quad”—the United States, European Union, Japan, and Canada—to reject the launch of a new round of negotiations.

By 2001, the WTO, and the United States and European Union in particular, had learned their lesson. First, the location chosen for the ministerial meeting was Doha, Qatar, a remote dictatorship where entry was controlled and protest illegal. Not only was it difficult for WTO-critics to get in to the country (only about sixty did), but it was also difficult for both the mainstream and alternative media to cover the event. The distance effectively blocked out the sunshine and gave negotiators the ability to wheel, deal, and arm-twist like never before.

Developing country delegates entered this ministerial virtually united in a set of demands consisting largely of reforms to existing WTO rules. They were united in their opposition to the launch of a new round and to the addition of new issues to the WTO’s already biased agenda. Also united were hundreds of citizens’ groups from around the world who had signed a WTO “shrink or sink” statement demanding the WTO not only reject new issues and the launch of a new round, but that it also “shrink” its current set of rules or “sink” as an organization all together. Once in Doha, however, all of these demands were quickly rejected and the unity of the developing country delegates was systematically destroyed.

Two weeks before the Doha ministerial began, U.S. Trade Representative Zoellick set the tone by saying, “as much as developing countries may need debt relief and development aid, a prerequisite for their long-term economic growth is full participation with the global economy and trading system. Doha is the best opportunity we will have in the next ten to fifteen years to expedite this integration. It is an opportunity neither we nor the developing world can afford to miss” (International Trade Daily, October 31, 2001). The not so hidden threat?—play ball in Doha or your debt relief and development aid will be cut off. This threat was spoken bluntly time and time again to developing country delegates in backrooms throughout Doha.

For example, according to Walden Bello, Executive Director of Focus on the Global South, Haiti and the Dominican Republic were told by the United States to cease opposition to one of the proposed new issues—government procurement—or risk cancellation of their preferential trade arrangements. Bello also describes how Pakistan, typically a stalwart among developing countries against the WTO, was mostly quiet in Doha after receiving a massive aid package of grants, loans, and debt reduction from the United States due to its special status in the U.S. war on terrorism. Also, Nigeria, which had issued an official communiqué denouncing the draft WTO declaration before Doha, came out loudly supporting it on November 14—a flip-flop that, according to Bello, is difficult to separate from the fact that the United States came up with the promise of a big economic and military aid package in the interim.

A Joint Motion for Resolution offered after the ministerial by members of the European Parliament states their opposition to the “heavy-handed and divisive tactics used by the WTO Secretariat, the EU, and the USA” in Doha.

Even more troubling to U.S. citizens may be how Zoellick abandoned promises he had made to senior United States senators such as John D. Rockefeller, Democrat from West Virginia. According to the senator, Mr. Zoellick “promised me, facing me, looking directly in my eye, in my office, that he would not in any way compromise various fair trade and anti-dumping laws, [and] he immediately did so within the first five minutes” of arriving in Doha (The Washington Post, December 17, 2001). Zoellick also chose to simply ignore Congress’ unambiguous statutory requirement that he seek a labor working group at the WTO.

The dirty politics worked: developing countries, isolated from information and support and in fragile positions due to the war on terrorism and the global recession, were brought to their knees; citizens groups were denied their numbers, access, and therefore much of their influence, and the launch of a new round was won. Upon departing Doha, Zoellick announced, “we have overcome the stain of Seattle” (International Trade Daily, November 15, 2001).

These dirty politics, however, look pristine in comparison to what came next—the vote on Fast Track. Fresh from his victory in Doha, Zoellick was prepared to do anything to complete his success by winning Fast Track.

The Fast Track Vote

On December 6, 2001, less than a month after the Doha ministerial, Fast Track was defeated in the U.S. House of Representatives. It had lost by four votes when the official time expired. Unfortunately, this is not the end of the story. Not to be undone by the rules, Robert Zoellick and the Republican leadership used their control of the House floor to keep the Fast Track vote open an unprecedented twenty-three minutes after the official clock expired. When they achieved a one vote majority, they slammed down the gavel: stopping the clock on the vote, eliminating the ability of the other side to respond, and eking out a 215 to 214 victory. Fast Track passed in the House.

In that twenty-three minutes, Republicans were searching for votes and found James DeMint, Republican of South Carolina waiting for them with a letter in his hand. The letter committed its signers (soon to include House speaker Dennis Hastert; Dick Armey, the majority leader; and Tom DeLay, the majority whip) to use “whatever means necessary” to cancel some textile export preferences already granted by Congress to Caribbean, Central American, and Andean nations in the Caribbean Basin Trade Preferences Act—effectively gutting a central provision of the Act—as well as directly contradicting pledges made by the United States in Doha to consider speeding the elimination of barriers to textile trade. With Democrats shouting to end the voting and declare defeat, DeMint and the House leaders engaged in animated discussions on the floor before DeMint got his letter signed. DeMint, who had voted no, then switched in his vote to yes. Then, according to DeMint, he “went and got a few other textile folks who were going the other way, and got them to vote for it. We passed it” (Los Angeles Times, December 2).

The tactics in Doha and Washington revealed the Bush Administration and House Republicans willingness to do anything to get their globalization agenda passed. To get a deal signed in Doha, they reneged on promises made to members of their own government and commitments required of them under U.S. law. To get a deal signed in Washington, they made the entire U.S. Congress renege on trade commitments made to some of the poorest countries in the world in an earlier trade agreement. Also in Washington, they reneged on commitments made in Doha to developing countries just weeks before. According to the conservative Financial Times, “the House vote [on Fast Track] casts doubt on Washington’s reliability as a partner.”

What it All Means

If it becomes law, Fast Track will allow the Bush administration to move any agreements reached in the WTO’s new negotiating round (as well as the FTAA and any other new trade deals) through Congress more easily. Included in the WTO negotiations (scheduled to conclude in 2005) are agreements—known as the “new issues”—desperately sought by multinational corporations in the areas of investment, government procurement, competition policy, and trade facilitation. Also included in the negotiations are “built-in” items such as services and agriculture. Similar agreements are included in the proposed FTAA. Both the new and built-in negotiations seek, through various channels, to allow multinational corporations greater access to markets—including many traditionally associated with governments—such as the provision of water, electricity, elementary and secondary education, libraries, waste disposal, etc.—while simultaneously restricting the ability of governments to regulate corporate behavior in these areas. In other words, the agreements force the United States, and all signatories, to move towards the privatization of these vital services without a single public discussion. The impact on the United States is the same as around the world—less government control, more corporate control, less accountability to citizens and their needs that run afoul of the profit motive.

At the writing of this article, Fast Track has not yet been passed. It must first go through the Senate and then most likely back to the House for a final vote. In addition, neither the FTAA nor any of the agreements being negotiated at the WTO are done deals (the next WTO ministerial meeting is scheduled for Mexico in 2003). We have the power to decide whether or not they come to be. Several pundits have already begun to argue that the dirty politics of the Doha ministerial and the vote on Fast Track could cost the Republicans their majority in Congress and their hold on the White House. Maybe it should.