Bechtel v. Bolivia

BECHTEL CORP. celebrated one of the most profitable years in its 100-plus-year history by suing one of the poorest countries in the world: Bolivia. After raking in $14 billion — nearly double Bolivia’s entire gross domestic product — San Francisco’s own multinational giant is suing the Bolivian government for $25 million. For its part, Bolivia celebrated the new year with $3 billion in external debt and with two-thirds of its population living in poverty.

BECHTEL CORP. celebrated one of the most profitable years in its 100-plus-year history by suing one of the poorest countries in the world: Bolivia. After raking in $14 billion — nearly double Bolivia’s entire gross domestic product — San Francisco’s own multinational giant is suing the Bolivian government for $25 million. For its part, Bolivia celebrated the new year with $3 billion in external debt and with two-thirds of its population living in poverty.

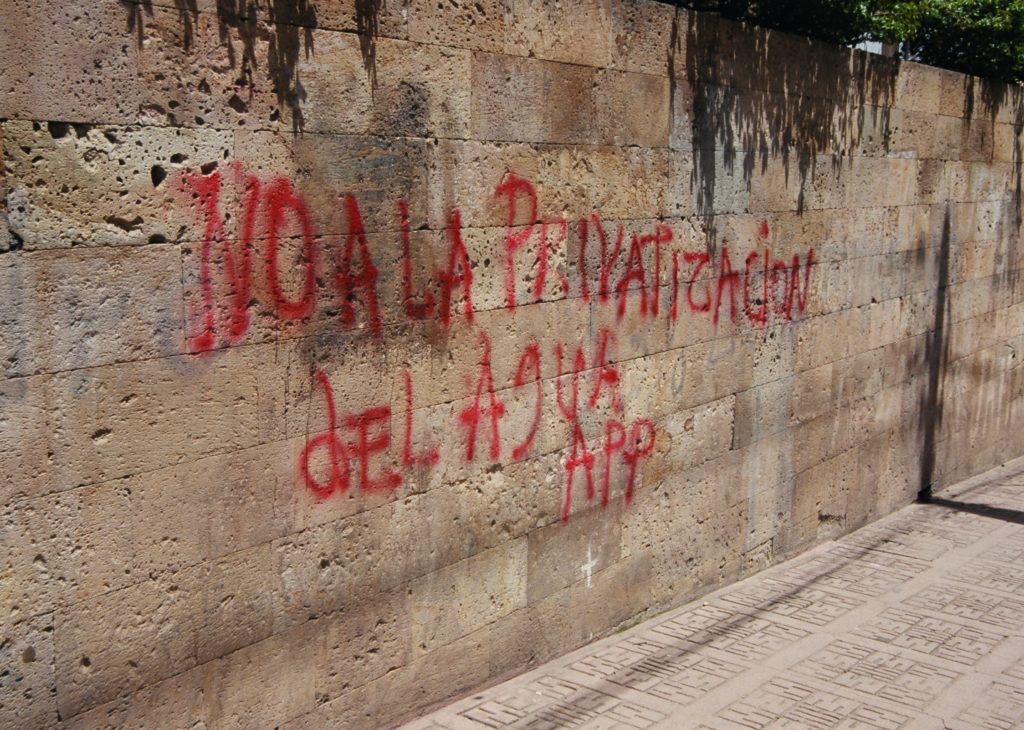

The reason why Bechtel is suing Bolivia is probably familiar to most readers. How they are doing it is probably not. As a reminder: In 1999, at the behest of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, Bolivia’s third-largest city, Cochabamba, privatized its water system. There was just one bidder: a consortium called Aguas del Tunari, whose controlling partner was International Water, a British firm that was then wholly owned by Bechtel (an Italian company later bought a half interest). Taking control of Cochabamba’s water was part of Bechtel’s plan to position itself as an international leader in water privatization, which also includes forming partnerships with other global water giants and investing billions of dollars to acquire interests in water privatization companies around the world. Bechtel is already a partner on many U.S. municipal water projects, including managing the reconstruction of San Francisco’s infrastructure.

After privatizing Cochabamba’s water, Aguas del Tunari raised fees. In a country where the minimum wage was less than $60 a month, many users received water bills of $20 a month and more. Families that had built and used their water wells or irrigation systems for decades suddenly had to pay Aguas del Tunari for this water. The people of Cochabamba united to cancel the contract.

One of their leaders, Oscar Olivera, will be in San Francisco next week to receive a belated Goldman Environmental Prize and join a protest at Bechtel’s headquarters Tuesday, April 23. After attempts at discourse with the government and the water company were ignored, the citizens nonviolently shut down the city. The government declared a state of siege, sending more than 1,000 soldiers into the streets armed with live ammunition, which resulted in the death of a 17-year-old boy, Victor Hugo Daza. Eventually the people prevailed, and the government agreed to end its contract with Aguas del Tunari and Bechtel. Most important, the workers, citizens, and local officials of Cochabamba are now running the water system themselves, while not perfectly, far more equitably and universally than before.

This could be our happy ending, but Bechtel wants its due. So it is using a Bilateral Investment Treaty to achieve its goal. The BIT is the predecessor to the investment chapter, Chapter 11, of the North American Free Trade Agreement. It is under Chapter 11 that the state of California is being sued for trying to protect our water from a cancer-causing chemical, MTBE, produced by the Canadian Methanex Corp.

Because the Free Trade Area of the Americas is not yet law (and hopefully we’ll keep it that way), Bechtel has no equivalent means to get at Bolivia. Fortunately for the company, it happens to have a holding company in the Netherlands, and the Netherlands just happens to have a BIT with Bolivia. Also conveniently, the BIT is argued at the World Bank’s own International Court for the Settlement of Investment Disputes. Remember that it was the World Bank that opened the door for Bechtel’s entry into Bolivia in the first place. Negotiations to include similar investment provisions at the World Trade Organization are currently under way. Bechtel’s suit gives us just one more reason to fight those agreements. Given the small amount of money involved in this suit — at least for Bechtel — we can only assume that it is meant as a warning to the people of the world, including San Francisco, not to follow the lead of Cochabamba’s “water warriors.” Are we going to listen?